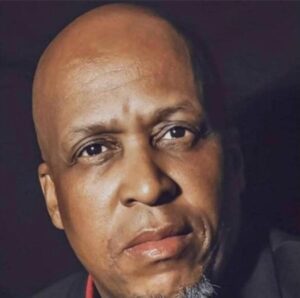

By: Clyde N.S Ramalaine

South Africa is poised to partake in its seventh democratic national electoral event since the negotiated settlement that produced its inaugural 1994 electoral moment. The announcement by President Ramaphosa to conduct the elections in May came as a surprise to me, as my earlier anticipation had been for August, taking into consideration the internal dynamics within the African National Congress (ANC).

I acknowledge my error in this regard. With the electoral date now established, it is opportune to address inquiries from those seeking guidance on voting choices.

Since 1999, I have refrained from affiliating with any political party, allowing my ANC membership to lapse. This deliberate decision has been motivated by a firm commitment to preserve my ability to openly express critical views without constraint. Despite this, my voting history until the era of President Ramaphosa reflects consistent support for the ANC. However, during this specific period, I opted for a protest vote in favour of the Black First Land First (BLF) movement.

I firmly believe that voters should comprehend their inherent power and agency, and consequently, they must resist feeling beholden to any particular political party. This autonomy empowers them to exercise their conscience, either by rebuking or rewarding policies and actions as they deem necessary for the advancement of South Africa.

It is pertinent to note my resolute decision to abstain, since 1999, from rejoining any political party or associating with a specific ideological stance, thereby refraining from affiliating myself with any party regalia. My approach to the act of voting has undergone an evolution, with a deliberate emphasis on prioritizing personal interests as the fundamental basis. I am steadfast in upholding a position of non-allegiance to any particular political party. Consequently, I affirm my right to impartially assess and scrutinize political parties, avoiding any sense of entitlement, as they actively vie for my vote. This stance is rooted in the recognition and maintenance of my agency to determine what is in the best interest of both my family and South Africa, as perceived from my unique vantage point.

My Public record of challenges with the PA

If I am to advise voters to vote for the PA, I am compelled to do so objectively and also transparently communicate my challenges with the PA for the record. It is duly recorded that I have publicly expressed disagreements with the Patriotic Alliance (PA) on a range of issues. Enumerated below, in no specific chronological order but of substantive concern, are nine noteworthy points:

- The establishment of an LGBTIQ League by the PA, driven by emotional and expeditious motives, raises concerns about the potential further marginalization of this group.

- The persistent absence of an organized structure in policy and infrastructure within the growing party inadvertently consolidates the president’s authority as the ultimate voice on PA matters in practical application.

- The PA’s overtly biased stance on Israel, without addressing the injustice inflicted on Palestine, where a significant Christian population resides, contradicts the principle of equality among people created by the same God professed by PA leaders.

- The party’s focus on targeting the church and its leadership, often culminating in agreements with pastors who later express dissatisfaction and accuse PA leadership, is a point of contention.

- While I support the PA’s unwavering stance on illegal immigrants, there is a notable absence of a well-thought-out, constitutionally aligned strategy for implementing this policy. Simply declaring the expulsion of all illegal foreigners upon assuming office lacks logical and sustainable justification.

- The PA, like other parties, should prioritize transparency regarding the sources of its funding. While legislative frameworks exist, true transparency remains elusive across political parties.

- The unfortunate deployment of members within the PA, similar to practices observed in the ANC and DA, raises concerns about skills deployment based on membership rather than merit. In Part 2, I will elaborate on my experience serving as an MTC Board member in the City of Johannesburg in 2020 on a PA ticket without being a member. I will further explore how the PA’s stance, despite acknowledging the undeniable skills of non-members, increasingly aligns itself with the ANC-led patronage system of reward.

- The allegations linking PA leaders with the notorious underworld also present a source of concern. I had anticipated a categorical condemnation of these claims from the PA leadership, accompanied by a clear disassociation from any such unsavoury associations. In my perspective, the deterrent effect on voters is not necessarily due to the veracity of these claims but rather stems from the PA’s perceived lack of a coherent strategy in addressing such allegations.

- Another disconcerting aspect is the hitherto absence of a political school within the PA, designed to impart the unique culture and ethos of the party to all incoming members. Nevertheless, it is imperative to acknowledge that the success of the PA is intricately tied to its leadership, with Gayton McKenzie occupying a central role.

In this two-part series, I will advocate a segment of South Africa’s populace still racially explained in State language and policy as ‘Coloured’ to consider endorsing the Patriotic Alliance in the upcoming elections on May 29, 2024.

Part 1, undertakes three primary objectives. Firstly, it gives a contextual analysis in overview of the historical voting patterns, delineating the essentially race-based nature of apartheid and democratic states’ political landscapes. This examination aims to elucidate the distinct and explicable party political footprints that emerged under both regimes. Secondly, it engages the ideology of minority politics, employing the late Amichand Rajbansi’s Minority Front as a prominent case study. This exploration seeks to elucidate the dynamics and impact of minority representation in a political context.

Lastly, it advances the argument that successive ANC-led states, by persistently adhering to an uphold of race rhetoric with uncritical identity markers of ‘African’, ‘Coloured’, ‘Indian’, and ‘White’ in defining its citizens, compel individuals and groups to engage in political ideology, formation, practices and thus exercise their democratic franchise inevitably entangled in the uncritically racial reality of South Africa.

Part 2 endeavours to provide a defensible justification for why the Patriotic Alliance (PA) offers hope for the Coloured community. This will be supported by practical examples illustrating the PA’s initiatives. It is pertinent to note that the author, having served as a Board Member and Chairperson of Service Delivery at MTC, one of the ten City of Johannesburg entities, from March 2020, may exhibit transparency as a beneficiary of the PA’s influence in power dynamics or coalition negotiations. The discussion will scrutinize the PA leadership’s assertion that they are actively pursuing power and are open to forming alliances with any political entity to secure such power. This ideological conviction will be dissected, and its rationality will be assessed within the context of race-based political parties.

Part 001: Why the Patriotic Alliance is justified to speak on behalf of South Africa’s coloured people in a space of racial party political interest?

Since the advent of democracy in South Africa in 1994, the nation has witnessed a complex and evolving landscape of voting patterns that reflect its diverse racial makeup. The democratic transition marked the end of apartheid, a system of institutionalized racial segregation, and ushered in an era of inclusivity. However, the legacy of apartheid still lingers in the minds of many, shaping the political preferences and voting behaviours of South Africans.

The South African voting patterns are intricately linked to the racial classifications established during the apartheid era, categorizing the population into four main groups: African, Coloured, Indian, and White. The post-apartheid state has actively promoted the idea of a rainbow nation, emphasizing unity in diversity. Nevertheless, the racial divisions persist, and they are evident in the voting choices made by different racial groups.

The African National Congress (ANC), historically positioned as the party that spearheaded the struggle against apartheid, has traditionally secured robust support from the demographic group it has, in a borrowed sense from the apartheid era, come to categorize as the ‘Black’ or ‘African’ population. The voting patterns within the ‘Coloured’ and ‘Indian’ communities, however, have exhibited notable diversity since 1994. Initially, substantial percentages of these communities supported the ANC, but over time, this backing has diminished. Presently, there is a discernible split, with some individuals within these communities continuing to align with the ANC, while others gravitate towards opposition parties, most notably the Democratic Alliance, which has emerged as a primary beneficiary of this shifting dynamic. In contrast, the ‘White’ population has consistently favoured political parties that align with their interests, notably the Democratic Alliance (DA) and the Freedom Front.

Understanding South African voting over the last 30 years requires an acknowledgment of the racial component that underscores this complex socio-political landscape. While strides have been made towards creating a unified nation, the persisting racial disparities in socio-economic factors contribute to the shaping of voting patterns. The challenge for South Africa moving forward lies in fostering a sense of common national identity while addressing the historical and ongoing racial inequalities that influence the choices made at the ballot box.

Examining the Western Cape as a geographic focal point for analyzing election voting patterns, several analysts have put forth various rationales for the electoral outcomes in this region. Schlemmer (1999, p. 288) posits that South African voter motivations are largely driven by ‘symbolic or identity concerns’, resulting in election outcomes resembling a ‘racial or ethnic census.’ On the contrary, Sniderman (2000, pp. 68-69) contends that political institutions, rather than voters, establish and organize the intricacies of politics. Daniel and Southall (2009, p. 268) attribute the choices made by political parties, particularly the ANC at a particular instance with Ebrahim Rassool and COPE with Allan Boesak, to the personality of Premier candidates. They assert that the ANC’s decisions related to Ebrahim Rasool were aimed at regaining support among Coloured voters, while the Congress of the People’s (COPE) selection of Allan Boesak dealt a substantial blow to the ANC due to his enduring influence, especially within the Coloured community. These perspectives raise the fundamental question of whether election outcomes in the Western Cape primarily result from the actions of voters or the strategic maneuvers of political parties.

I wish to assert that the issue of racial group identity is an incontrovertible reality, stemming not merely from individual choices or preferences of perspectives, but predominantly from the successive expressions of the democratic state since 1994. The state, driven by its imperative for redress, has unquestioningly confined the South African citizenry within susceptible racial identity markers. Regardless of alternative explanations posited by analysts, the role of the state as paradigmatic in shaping social identities remains a central and indispensable component, serving as a lens through which election dynamics ought to be comprehended. It appears imprudent to predicate race in group classification as a basis for identity markers and subsequently dismiss its significant influence in political formations, the establishment of political parties, and the delineation of group interests.

The aphorism “Do not despise small beginnings” resonates as an ancient biblical maxim that involuntarily imposed itself upon my contemplation when scrutinizing the evolving dynamics of South African politics, particularly at the local government level, with the Patriotic Alliance (PA) as a noteworthy participant. The political terrain is inherently mutable, and while the African National Congress (ANC) has celebrated victories since the onset of democracy, emerging parties, initially diminutive and seemingly inconsequential against the backdrop of the broader political economy, have altered the canvas of South African politics.

It is plausible to conjecture that post-May 29, 2024, the ANC may experience a loss of control over additional provinces, with KwaZulu-Natal, Gauteng, North-West, Mpumalanga, and the Northern Cape being particularly susceptible to a shift from ANC majority. Such a scenario implies a potential transition towards a more federal or provincial identity of governance for South Africa, wherein the ANC, if retained in power, would owe its incumbency to the delicate nature of coalition agreements. The contemplation of an ANC administration operating nationally with less than five of the nine provinces under its dominion necessitates a thorough examination of the potential implications and repercussions that may arise in such a political landscape.

Minority Representation Amichand Rajbansi Political Strategy

Scholarly discourse on minority representation posits that it fortifies representational bonds, fostering positive attitudes towards government and encouraging political engagement. Current scholarship contends that minorities achieve equitable representation in single-winner districts when the minority population is politically homogeneous and geographically concentrated, as suggested by Welch (1990) and Casellas (2009) in their analyses of Hispanic populations. South Africa’s democratic trajectory underscores a shift in focus from national seats in parliament to local government over the past 26 years. Local government, representing the crucible of community concerns, assumes paramount importance. The ANC’s neglect of this sphere, essential for governance, reveals a fundamental error, as local government encapsulates the nexus of citizenry and government, embodying the presence or absence of service delivery.

A modulated exploration of post-settlement South African minority politics finds resonance in the regional contributions of the late Amichand Rajbansi and his Minority Front concentrated in Kwa-Zulu Natal. Initially disparaged as racially charged, inconsequential in numerical terms, and somewhat cynical, Rajbansi’s political endeavours now reveal a more profound understanding, echoed in the subsequent work of the Patriotic Alliance. Although the efficacy of minority representation in working for its constituency may not always be readily apparent, Rajbansi’s ideology, strategy, and tactics serve as a foundation for understanding this political trajectory.

Rajbansi’s ideology rested on the belief that minorities, despite their numerical inferiority, can wield influence where it matters. Recognizing the concentration of Indians, historically linked to the garment industry, mainly in Natal and later in KwaZulu-Natal under democracy, Rajbansi acknowledged that numerical superiority against the ANC was unattainable. Consequently, he positioned himself as a powerbroker with regional prominence, engaging with any political party to influence election results shaped by race classification preferences. Rajbansi astutely recognized that Indians, as a group, did not align with the ANC, leading him to target those within his community who refrained from supporting the ANC, National Party, or Democratic Party at the time. His strategic approach involved creating a political vehicle to carry the mandate on behalf of those who did not favor the aforementioned parties. Rajbansi’s tactics involved engaging with his people, speaking their language—both figuratively and literally—by understanding that Indian communities communicate in their traditional languages (e.g., Gujarati). He addressed their concerns as ratepayers, asserting their rights enshrined in the constitution. Despite facing accusations of exclusivism, racism, and self-serving motives, particularly from politically connected Indian elites within the ANC, Rajbansi’s calculated approach allowed him to be a significant power broker, impacting outcomes at regional, provincial, and, to a lesser extent, national levels.

Amichand Rajbansi founded the Minority Party in KwaZulu-Natal with a distinct focus on representing the interests of the Indian community within the broader political landscape of South Africa. Recognizing the relatively small percentage of the population that the Indian community constituted, particularly in comparison to the majority African population, Rajbansi sought to establish a political entity that could serve as a dedicated voice for the concerns and aspirations of the Indian minority. The intention behind the formation of the party was rooted in the belief that a specific platform was essential to effectively advocate for and negotiate the unique interests of the Indian community within the proverbial sea of African majority, ensuring that their needs and perspectives were not overlooked in the democratic process. Through the Minority Party, Rajbansi aimed to provide a platform for meaningful representation and bargaining power for the Indian population in the complex socio-political landscape of post-apartheid South Africa

The Patriotic Alliance, established in 2013 and marking its eleventh year of active politics, has actively participated in critical provinces and municipalities, displaying gradual but notable results. The PA’s anchor base includes representation in the Western Cape – Beaufort West, Nelson Mandela Metro, City of Joburg Metro, Ekurhuleni, Tshwane, and Cape metros. Notably, the PA’s decision to support the Democratic Alliance’s Atholl Trollip against the Economic Freedom Fighters’ (EFF) opposition, led by Kenny Kunene, exemplifies principled decision-making in navigating race politics. The PA’s business case for its anchor base is justifiable, considering the disenfranchisement, economic deprivation, and lack of social identity agency faced by the Coloured community, a group that has been overlooked in terms of service delivery, job opportunities, economic participation, equality, and development.

The enduring colloquialism, “first-not-white-enough-now-not-black-enough,” succinctly captures the predicament of the Coloured community, which, despite being classified and stratified since 1994, experiences ongoing disenfranchisement. The ANC’s uncritical adoption of apartheid-era lexicon has perpetuated the fallacy of race as a social construct, inadvertently reinforcing discriminatory practices. While the Coloured community exhibits diverse identity articulations, the democratic state’s adoption of apartheid-era labels without critical engagement has contributed to their continued disenfranchisement. The Patriotic Alliance, recognizing the necessity and duty to respond to the economic disempowerment of ‘Coloured’ communities, has organically chosen to raise its banner in addressing these real challenges.

Acknowledging the Patriotic Alliance’s existence as a response to economic disenfranchisement akin to apartheid victims and, more specifically, the ‘Coloured’ identity markers, underscores the centrality of this contextual reality to the party’s raison d’être. While challenges may be raised, the PA’s response to economic disenfranchisement, within the frame of Coloured definition, positions it as a player in the local governance index of minority parties. In essence, the Patriotic Alliance must be understood and interpreted within the context of a political entity responding to the imperative of redressing historical economic marginalization, particularly as experienced by the Coloured community.

I distinctly recall authoring an unsolicited discussion document in around 2019/2020 concerning the imperative for the Patriotic Alliance (PA) to delineate its focus. In the alluded document, I argued that the PA’s strategic positioning was not a matter of choice but an exigency dictated by the prevailing political landscape, voting patterns in South Africa since 1994, and the undeniable disenfranchisement experienced by Coloureds as a collective. Notably, I highlighted a disconcerting statistic indicating that the likelihood of a Coloured male youth securing employment in South Africa stands at a mere 14.1%. This document was communicated to PA leader Gayton McKenzie, who initially expressed disagreement with the notion that the PA must unequivocally centre its mission on the advancement of Coloureds. In response, I encouraged him to review the document. It is now a matter of historical record that the PA explicitly represents the Coloured constituency as its central focus, concurrently demonstrating a commitment to inclusivity by appointing individuals from all racial backgrounds to positions of influence whenever empowered to do so.

In light of the state’s classification of individuals and a group as ‘Coloured’ and the inherent race-informed characteristics of South Africa’s voting patterns, a critical examination of the political landscape reveals a dearth of parties that have distinctly addressed the historical legacies perpetuated by both apartheid and successive ANC-led states’ preoccupation with race as a means to explain its citizens and the impact on those it continues to classify and identify as belonging to a ‘Coloured’ race. In this context, a viable alternative emerges in the form of the Patriotic Alliance (PA), prompting one to contemplate the imperative of supporting a party that may be positioned to challenge prevailing narratives and advocate for the nuanced concerns associated with the Coloured community.