By: Clyde N.S Ramalaine

- Introduction

The role of religion and faith in foreign diplomacy has often been overshadowed by economic, political, and security concerns. However, historical and contemporary examples demonstrate that religion is a central force shaping international relations. This article aims to highlight how faith and religious identities are not only ever-present but often serve as primary motivators behind state-led actions and advocacy efforts. By moving beyond traditional secular interpretations of diplomacy, this analysis acknowledges the potent influence of religious beliefs in shaping foreign policy decisions.

Employing the theoretical framework of religious realism, this article examines the intersection of faith and diplomacy within the contexts of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam as three predominant religions that define the context and space of the analysis both in historical and contemporary unfolding realities.

Our approach begins with a broad historical reflection on the role of religion in diplomacy, tracing key meandering moments where faith took centre stage in shaping international relations. From past incidents where religious identity and ideology influenced diplomatic outcomes to contemporary case studies, we seek to uncover the often-overlooked dimensions of faith in geopolitics.

As case studies, we will examine the complex relationship with religion as an attending factor between the United States and Israel, focusing on their established alliance and commitment to safeguarding Israel against what is commonly framed in discourse as hostile Muslim-majority nations. This analysis will consider the broader religious and political dynamics shaping their interactions on the global stage. Additionally, we will explore the ongoing Israel-Palestine conflict through the lens of its religious dimension and the armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine, with particular attention to the underlying religious influences that contribute to these impasses.

A focal point of our analysis will be South Africa’s role in the Israel-Palestine case before the International Court of Justice (ICJ). This case is particularly significant, as it elevated South Africa beyond symbolic solidarity and humanitarian advocacy, positioning it as a distinguishing key player in the legal discourse surrounding the conflict. Beyond the obvious legal and political dimensions, we will interrogate a deeper, often-neglected question: Did the faith identities of key South African political figures influence the country’s decision to take up this cause? By unpacking this question, we aim to shed light on the intersection of religion, law, and diplomacy in a way that challenges conventional narratives.

- Religious Realism and Its Theological Moorings

Religious realism asserts that while religions function as psychological and sociological constructs, they also make truth claims about reality, particularly concerning metaphysical entities such as God. This perspective underscores how religious doctrines shape global diplomatic engagements and policy formulations Religious realism holds that faith-based beliefs are not merely subjective or symbolic but assert fundamental truths about existence. Within this framework, the following theological concepts illustrate the interplay between religion and realism for the three pre-dominant Abrahamic faith streams:

2.1 Christianity

In Christianity, religious realism is exemplified in the doctrine of the incarnation, which asserts that Jesus Christ is both fully divine and fully human. This is not understood merely as a metaphorical or symbolic belief but as an ontological reality – that God took on human flesh in the person of Jesus. The Incarnation reinforces the realist perspective that religious beliefs in Christianity are not just abstract or psychological constructs but assert fundamental truths about the nature of existence. This realism extends to doctrines such as the resurrection, which is regarded not as a spiritual allegory but as a historical and physical event with significant implications for salvation and the afterlife.

The doctrine of the Incarnation which asserts that Jesus Christ is both fully divine and fully human, reinforces the realist perspective that religious beliefs intersect with tangible reality. Similarly, the Resurrection is viewed not as a metaphor but as a historical event with significant implications for salvation and the afterlife.

2.2 Judaism

The concept of Divine Covenant, particularly the belief that God made an enduring covenant with the people of Israel, exemplifies religious realism. Orthodox Jewish thought holds that the Torah, given to Moses at Mount Sinai, contains divine laws with objective authority, shaping Jewish claims to the land of Israel and influencing geopolitical debates. This is not merely a symbolic or cultural idea but a truth-claim about reality. Orthodox Jewish thought holds that God literally gave the Torah to Moses at Mount Sinai, and its commandments (mitzvot) are not human constructs but divine laws with objective authority. The belief that the land of Israel was divinely promised to the Jewish people further demonstrates religious realism, as it asserts a metaphysical truth with concrete political and territorial implications.

2.3 Islam

Tawhid (the oneness of God) and the belief that the Qur’an is the literal, uncreated word of God highlight religious realism in Islam. Furthermore, the belief in the Day of Judgment and divine justice (Adl) reinforces faith as an objective and absolute reality, guiding Islamic perspectives on governance, law, and diplomacy. This is not regarded as a subjective or allegorical expression but as an objective and absolute reality. The concept of divine justice (Adl) in Islamic theology, particularly in Shi’a Islam, also exemplifies religious realism, as it posits that God’s justice is not an abstract ethical principle but an inherent, ontologically fundamental attribute that governs the universe. Additionally, the belief in the Day of Judgment (Yawm al-Qiyamah) is an assertion of an eschatological reality that exists beyond human perception but is nevertheless regarded as an absolute truth.

This exploration hopes to not only provide a different perspective on South Africa’s involvement but also offer a broader framework for understanding how faith continues to shape global diplomacy in ways that are frequently underestimated or misunderstood. In this regard, it will focus on selected case studies for its articulation.

3. The Case Studies

- America’s Support for Israel vs. Israel’s Muslim Enemies – The strong U.S.-Israel alliance is influenced not only by geopolitical interests but also by religiously motivated Christian Zionist support. Conversely, Muslim-majority nations opposing Israel do so not only on political grounds but also based on Islamic solidarity with Palestine.

- The Israel-Palestine Conflict – Both Jewish and Muslim religious identities are deeply embedded in the struggle over land, self-determination, and governance.

- The Russia-Ukraine War – The influence of Orthodox Christianity, particularly the ideological divide between the Russian Orthodox Church and the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, plays a crucial role in nationalistic narratives and justifications for war.

- South Africa’s ANC-Led Diplomatic Action Against Israel in the ICJ – South Africa’s historical struggle against apartheid influences its solidarity with Palestine, but the faith identities of key decision-makers throughout and in particular at the time of the ICJ litigation also inform its approach in ways that demand scrutiny.

4. Religion in Diplomacy – A Cursory Overview

Historically, religion has played a fundamental role in shaping diplomatic relations. The Peace of Westphalia (1648), which ended the Thirty Years’ War, was rooted in religious conflicts between Protestant and Catholic states. The war demonstrated how deeply intertwined religious identity and political power were, leading to a diplomatic framework that sought to separate faith from statecraft. However, despite this formal separation, religious affiliations continued to influence European alliances and rivalries, shaping the continent’s power dynamics for centuries.

Similarly, the Ottoman Empire’s interactions with European powers were deeply influenced by Islamic governance principles. The Ottoman Caliphate positioned itself as both a political and religious authority, negotiating treaties and military alliances based on religious solidarity or opposition. The empire’s ability to integrate diverse religious communities under the Millet system showcased how faith could be a tool for diplomatic flexibility, yet also a justification for war, particularly in conflicts with Christian European states.

The Vatican has also been a crucial diplomatic player, mediating conflicts and shaping moral narratives on international issues. As the seat of the Catholic Church, the Vatican has historically exerted soft power through its moral authority, influencing the policies of Catholic-majority nations. From the role of papal envoys in European politics to more contemporary interventions in peace processes, the Vatican’s involvement in diplomacy demonstrates how faith-based institutions wield significant influence in global affairs.

Beyond these examples, religion has consistently played a role in international relations, often determining alliances, conflicts, and resolutions. While modern diplomacy often attempts to sideline religious considerations in favour of secular state interests, the historical record shows that faith remains an enduring and powerful force in shaping foreign policy decisions. As such, acknowledging the role of religion in diplomacy is not just an academic exercise but a necessary and significant step toward understanding the motivations and consequences of global political actions.

The principal objective of this article is to demonstrate that faith and religious narratives and identities are ever-present and, in many cases, the primary driving force behind state-led actions and support-based advocacy. This analysis seeks to move beyond the traditional secular framing of diplomacy by acknowledging the potency of religious beliefs in shaping foreign policy decisions.

5. Historical Incidents Where Religion Adopted The Epicentre Role

The following, though not an exhaustive list of historical incidents, illustrate how faith has been instrumental in foreign diplomacy:

- The Crusades (1095–1291)

A series of religious wars initiated by the Catholic Church to reclaim the Holy Land from Muslim rule, demonstrated how faith served as a primary motivator for military and political engagement.

The Crusades were driven by religious zeal, as Pope Urban II called upon European Christians to reclaim Jerusalem from Muslim control. These campaigns were fueled by the belief that fighting in the Crusades would secure divine favour and absolution from sins. Beyond religious motivations, political and economic interests played a role, as European monarchs sought territorial expansion and wealth. The result was centuries of conflict between Christians and Muslims, reinforcing deep religious animosities that persist in some geopolitical tensions today. The Crusades also led to the establishment of Christian states in the Levant, which were short-lived but influenced the strategic and religious outlook of European powers.

5.2 The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494)

An agreement brokered by Pope Alexander VI, divided newly discovered lands outside Europe between Spain and Portugal, showcasing how religious authority influenced global territorial arrangements.

The treaty was a papal intervention to resolve disputes between Spain and Portugal over newly discovered lands. Rooted in the Catholic Church’s authority, it demonstrated how religious figures shaped international diplomacy. By granting Spain dominion over most of the Americas and Portugal control over Brazil and parts of Africa and Asia, the treaty reinforced Catholicism’s role in colonization. The division of lands led to the aggressive missionary activities of both nations, spreading Christianity globally. It also established a precedent where European imperialism was justified by religious mandates, significantly shaping the religious and cultural identities of colonized territories.

5.3. The Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648) and the Peace of Westphalia

A conflict primarily between Protestant and Catholic states in Europe, highlighting how religious affiliations fuelled warfare and subsequently reshaped the European diplomatic order.

Initially triggered by tensions between Protestant and Catholic states in the Holy Roman Empire, the Thirty Years’ War escalated into a broader European conflict involving political power struggles. The war saw shifting alliances where even Catholic and Protestant states at times aligned based on national interests rather than religious affiliation. The devastation of the war led to the Peace of Westphalia, which established the principles of state sovereignty and religious tolerance, reducing the influence of religious authority in European politics. However, the war demonstrated how deeply religious identity was entangled with political legitimacy and statecraft, reinforcing the need for balancing religious and secular governance in diplomacy.

5.4 The British and French Mandate System (1919)

Colonial powers, influenced by religious and cultural biases, structured their governance of the Middle East, leaving long-term religious and sectarian impacts on diplomacy in the region.

After World War I, Britain and France assumed control over former Ottoman territories under the League of Nations Mandates. These powers often governed through sectarian divisions, favouring certain religious groups over others to maintain control. The British encouraged Jewish migration to Palestine, aligning with Zionist aspirations, while simultaneously making promises to Arab leaders, sowing the seeds for future conflict. The French divided Lebanon and Syria along sectarian lines, exacerbating divisions between Christians, Sunnis, and Shi’a. The mandate system not only reshaped Middle Eastern geopolitics but also reinforced religious identities as a basis for political organization, contributing to persistent conflicts in the region.

6. America’s Support for Israel vs. Israel’s Muslim Enemies

The U.S.-Israel alliance is deeply rooted not only in strategic and geopolitical considerations but also in religious convictions, particularly the influence of Christian Zionism. Many American evangelical Christians believe in the biblical prophecy that ties the existence of Israel to divine will and the Second Coming of Christ. This theological perspective has translated into unwavering political support for Israel, influencing U.S. foreign policy decisions, military aid, and diplomatic backing in international forums. This religious dimension ensures that U.S. support for Israel is not merely transactional but ideological, reinforcing a commitment that transcends changing political administrations.

Conversely, Israel’s opposition from most Muslim-majority nations is not solely political but is also steeped in Islamic solidarity with Palestine. For many in the Islamic world, the Palestinian cause is viewed through the lens of religious duty, with Jerusalem’s Al-Aqsa Mosque holding profound spiritual significance in Islam. The conflict is framed as a struggle between an Islamic heritage and what is perceived as Zionist expansionism, leading to widespread support for Palestinian resistance movements. Islamic clerics, political leaders, and grassroots movements rally around this narrative, reinforcing the conflict’s religious undertones.

This intersection of faith and politics ensures that the U.S.-Israel alliance, and its opposition by Muslim states, is not merely about territorial disputes or strategic interests. Instead, it is a discerning ideological and theological struggle, making diplomatic resolutions increasingly difficult. When religious beliefs fuel national policies, they create a moral dimension that resists compromise, as both sides see their positions as divinely sanctioned rather than politically negotiable.

7. The Israel-Palestine Conflict

The Israel-Palestine conflict is often framed as a geopolitical and territorial dispute, yet at its core, it remains deeply rooted in religious narratives, historical claims, and theological convictions. The land in question holds profound significance for Judaism, Islam, and Christianity, with competing religious claims shaping national identities and justifications for sovereignty. For Israel, the notion of a Jewish homeland is inseparable from biblical promises and Zionist ideology, which draws upon religious and historical narratives to assert legitimacy.

Conversely, for Palestinians, particularly Muslim communities, the land is not only a national territory but also a sacred space, with Jerusalem and Al-Aqsa Mosque holding immense religious importance. Religious institutions, leaders, and texts continue to influence perspectives on both sides, reinforcing the inextricable link between faith and the conflict. Consequently, while political, economic, and strategic factors are often highlighted, religious belief remains a foundational force shaping the discourse, grievances, and aspirations of both peoples.

Given the centrality of religion to the conflict, those who support either Israel or Palestine inevitably engage with religious identities and defences, whether consciously or subconsciously. For Jewish and Christian Zionists, support for Israel is often framed in theological terms, with references to divine covenants and eschatological beliefs.

Similarly, Muslim solidarity with the Palestinian cause is deeply informed by religious duty, a sense of Islamic brotherhood, and the sanctity of the land. Even secular supporters of either side cannot fully detach from the religious dimensions that shape narratives of justice, resistance, and belonging. International diplomatic efforts, too, are coloured by religious underpinnings, as nations with strong religious identities—whether Western Christian-majority states or Muslim-majority countries—navigate their policies through the lens of faith-based allegiances. Thus, to engage with the Israel-Palestine conflict is, by necessity, to engage with religious worldviews, making neutrality a complex and often illusory stance.

The Israel-Palestine conflict is, therefore, one of the most vivid examples of how religion influences foreign diplomacy. The pro-Israel stance, largely driven by Jewish religious and historical claims to the land, finds strong support among Christian Zionists, particularly in the United States. On the other side, Palestinian nationalism is deeply intertwined with Islamic and Christian identities, with many Arab nations framing their support for Palestine as a defence of Muslim rights and heritage.

For pro-Israel advocates, the establishment and defence of Israel are tied to biblical prophecies and historical Jewish suffering, making faith a foundational argument for their geopolitical positioning. Meanwhile, supporters of Palestine, particularly in the Muslim world, invoke religious duty to uphold the Palestinian cause, often viewing it as a struggle against oppression with theological underpinnings. The presence of faith leaders, religious rhetoric, and religious sites in the conflict further solidifies the inescapable role of faith.

The Israel-Palestine conflict is often framed as a territorial and nationalist struggle, but at its core, it is deeply interwoven with Jewish and Muslim religious identities. For Jews, Israel is not merely a state but the fulfilment of biblical prophecy—a return to the Promised Land granted by divine covenant. The religious Zionist movement sees the establishment and expansion of Israel as an obligation tied to Jewish eschatology, making territorial concessions not just a political question but a theological one.

For Muslims, Palestine is not simply a homeland but a sacred territory that includes Al-Quds (Jerusalem), one of Islam’s holiest cities. The Al-Aqsa Mosque is not only a place of worship but a symbol of Islamic heritage and resistance. Palestinian nationalism is thus fused with religious significance, and groups such as Hamas derive legitimacy from Islamic doctrine that frames resistance as both a political and spiritual duty. This fusion of religion and identity means that the conflict is not just about land—it is about religious sovereignty and existential legitimacy.

Attempts at resolving the conflict have consistently faced obstacles due to this religious dimension. Secular diplomatic initiatives often ignore or downplay the theological convictions that fuel both Jewish and Muslim perspectives on the land. Any meaningful resolution must acknowledge that religious realism—not just nationalism or geopolitics—is a key factor in sustaining the conflict. Without addressing the deeply held religious convictions on both sides, peace efforts will remain superficial and ineffective.

8. The Russia-Ukraine War

The Russia-Ukraine war is frequently analysed through the lens of territorial ambitions, historical grievances, and geopolitical rivalries. However, Orthodox Christianity plays a pivotal role in shaping nationalistic narratives on both sides. The Russian Orthodox Church, under Patriarch Kirill, has positioned itself as a staunch supporter of Vladimir Putin’s policies, framing the war as a struggle for spiritual and civilizational unity. Russian Orthodoxy sees Ukraine as an integral part of “Holy Rus,” a religious and historical unity that predates modern nation-states.

In contrast, Ukraine’s assertion of independence has been reinforced by the split within Orthodox Christianity. The establishment of the independent Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU) in 2018, recognized by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, was a significant moment in breaking religious ties with Moscow. This schism was not merely ecclesiastical but political, as it reinforced Ukraine’s sovereignty and resistance against Russian influence. The religious dimension thus fuels the conflict, as both sides see their struggle as part of a broader spiritual and historical battle.

The war’s religious underpinnings add a moral justification to Russia’s aggression and Ukraine’s resistance. It is not simply a war over borders but a fight over religious identity and civilizational belonging. The presence of Orthodox symbols, clerical endorsements, and religious rhetoric in state propaganda on both sides underscores that faith is not a secondary factor but a central force in shaping perceptions and justifications for war.

9. South Africa’s ANC-Led Diplomatic Action Against Israel in the ICJ

South Africa’s recent fulcrum moment of diplomatic action against Israel at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) is largely understood through its historical lens of anti-apartheid solidarity with Palestine. The ruling ANC government has long drawn parallels between South Africa’s past struggles and the Palestinian cause, framing its stance as one rooted in historical justice and human rights. However, what is often overlooked is the role of faith identities within South Africa’s leadership in shaping this diplomatic engagement.

Key figures in the ANC government, including ministers, officials and diplomats, openly identify with religious traditions that inform their moral perspectives on global conflicts. The influence of liberation theology, a Christian framework that fuses faith with social justice, is evident in South Africa’s diplomatic rhetoric. The argument against Israel is thus not purely political but is underpinned by a moral-theological stance, where opposing perceived oppression is seen as a religious duty.

Furthermore, South Africa’s engagement is shaped by its diverse religious landscape, which includes strong Muslim communities that have historically aligned with the Palestinian cause. The interplay of Islamic solidarity, Christian liberation theology, and African traditional values creates a uniquely faith-informed foreign policy stance. Recognising this religious dimension is crucial in understanding why South Africa has taken such a bold position, and why its diplomatic choices are not merely a matter of political ideology but are deeply rooted in moral and spiritual convictions.

9.2 The 2024 ICJ Case A Fulcrum Moment in South African Diplomacy

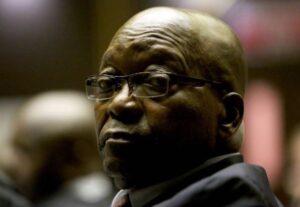

The decision by the South African government to bring a case against Israel at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 2024 was not merely a diplomatic manoeuvre; it was a historic fulcrum moment in post-apartheid South Africa’s international relations. While successive administrations, from Nelson Mandela’s to Jacob Zuma’s, had maintained a consistent pro-Palestinian stance, none had previously pursued legal recourse at an international tribunal of this magnitude. President Cyril Ramaphosa’s administration took an unprecedented step, shifting South Africa’s Palestine policy from rhetorical and diplomatic opposition to a formal legal challenge under international law. This move signified a profound evolution in South Africa’s foreign policy, compelling the international community to reckon with its longstanding moral and legal positions.

9.3 The Legacy of South African Leaders in Palestine

Since the dawn of democracy in 1994, South Africa has vocally championed the Palestinian cause. Nelson Mandela, in his Ted Koppel New York City interview, famously equated the struggle of the Palestinians with that of South Africans under apartheid, declaring that South Africa’s freedom was incomplete without the liberation of Palestine. Thabo Mbeki further reinforced this position, arguing that the same moral imperatives that guided the anti-apartheid movement should guide global solidarity with Palestine. Jacob Zuma, known for his alignment with South Africa’s leftist factions, also upheld a strong anti-Israel stance, ensuring that South Africa distanced itself from Israeli political and economic engagements. However, despite their firm rhetoric and consistent opposition to Israeli policies, none of these leaders took the decisive legal action that Ramaphosa and his administration ultimately did in 2024.

While the proverbial jury is still deliberating on the efficacy and value of such a diplomatic choice—an issue I intend to explore in a future article—we must, for now, acknowledge that Ramaphosa on face value stands in a league of his own in this regard.

9.4 A Shrouded Process – The Mystery of Decision-Making

According to the summary of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) proceedings on 26 January 2024, the Court was addressing an application concerning the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in the Gaza Strip (South Africa v. Israel). On 29 December 2023, South Africa submitted an application to the Court’s Registry, initiating proceedings against Israel for alleged violations of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (hereinafter referred to as the “Genocide Convention” or the “Convention”).

On Friday, 26 January 2024, during a televised address, President Ramaphosa delivered the following opening remarks: “Fellow South Africans, Earlier today, the International Court of Justice in The Hague issued a ruling that represents a victory for international law, human rights, and, above all, justice. This ruling follows South Africa’s unprecedented decision to bring another country before the International Court of Justice.”

However, in public discourse, the precise origins and behind-the-scenes mechanics of South Africa’s decision to bring a case against Israel before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) remain largely concealed from public view. The internal deliberations, strategic calculations, miscalculations, and the sense of urgency that culminated in this legal action are shrouded in ambiguity. What specific legal and political considerations prompted the government to escalate its stance from diplomatic condemnation to formal litigation on the international stage? What diplomatic contingencies were weighed, and what geopolitical consequences were anticipated? Who were the external stakeholders, and what were their direct or indirect roles? What role did the Palestinian Government play in discussions with South Africa? Furthermore, why was South Africa’s action against Israel not fully endorsed by Middle Eastern nations, the broader Arab community, or a significant contingent of African nations? Additionally, why is South Africa’s action perceived in the context of allegations regarding Iranian sponsorship?

While politicians and state officials have justified the move as both a moral imperative and a legal necessity, the absence of citizen participation and transparency regarding the decision-making process raises important questions. This lack of clarity does not necessarily undermine the legal validity of the case itself, but it does warrant a critical examination of the motivations and procedural mechanisms that led to its pursuit at this particular juncture. In a political landscape where international litigation carries profound diplomatic and economic implications, the opaqueness surrounding this decision invites scrutiny—not only of the case’s legal foundations but of the broader strategic interests that may have influenced South Africa’s unprecedented step.

It cannot be that, in a moment of collective sentiment, we allow ourselves to romanticise this decision while choosing to be absent from a critical evaluation of the underlying forces that drove it. Are we to wait until a politician pens a memoir to gain insight into the rationale behind this pivotal moment, or do we, as South Africans, have the right to demand transparency? We must ask how this decision was initiated, who the key role players were, what deliberations took place, and ultimately, how this course of action was determined. In a democratic society, such scrutiny is not only justified but essential.

9.5.The Role of Religious Persuasion in Foreign Policy Decision-Making Influence, Obligations and Strategic Calculations

Beyond structural and diplomatic considerations, an often-overlooked yet critical dimension of foreign policy decision-making lies in the personal convictions of those who occupy key government positions. In the case of South Africa’s legal challenge against Israel at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), an important, albeit sensitive, question arises: to what extent did the religious identities of pivotal political officeholders influence the decision to escalate South Africa’s position from diplomatic rhetoric to formal litigation?

9.5.1 Faith and Foreign Policy: The Influence of Officeholders

Let me state upfront that highlighting the religious affiliations of politicians and officials is neither a trivial personal attack nor an ad hominem argument nor does it deny their constitutionally protected rights. Rather, it serves to contextualise foreign diplomacy, where religion operates as a dynamic and influential factor.

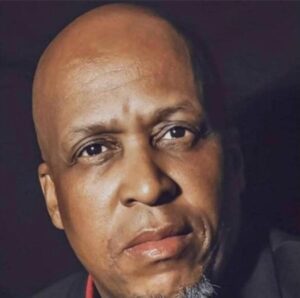

Dr. Naledi Pandor, South Africa’s Minister of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO) at the time, and Mr. Zane Dangor, the serving Director-General of DIRCO, are both practising Muslims. While foreign policy is officially formulated within a secular framework, it is impossible to entirely disentangle personal convictions from political decision-making. Religion shapes moral worldviews, frames conceptions of justice, and informs the ethical obligations that leaders may feel toward international causes. Given that Islamic solidarity with the Palestinian cause has been a longstanding feature of global Muslim political consciousness, it is reasonable to critically examine whether Pandor and Dangor’s religious orientations influenced South Africa’s diplomatic stance—either explicitly or at a subconscious level.

9.5.2 The Intersection of Islamic Solidarity and South African Diplomacy

South Africa has historically positioned itself as an advocate for Palestinian rights, drawing comparisons between the Israeli occupation and its own experience with apartheid. However, while this stance is often framed as a legacy of anti-colonial solidarity, it is worth investigating whether the personal commitments of key decision-makers added a dimension of religious moral urgency to this particular intervention.

Islamic teachings emphasise a duty of solidarity (Takaful) among Muslims, particularly in situations where fellow believers are perceived to be oppressed. Political figures who are devout in their faith often carry a heightened sense of moral responsibility, which can manifest in policy decisions that align with religious imperatives. While Pandor and Dangor would never officially cite their faith as a determinant of South Africa’s foreign policy, the broader geopolitical reality suggests that religious identity can—and does—play a role in shaping diplomatic priorities, especially in cases where secular political considerations and faith-based convictions align.

9.5.3 Religious Affiliation as a Facilitative Tool in Diplomatic Negotiations

A critical yet underexplored aspect of South Africa’s decision to take Israel to the ICJ is the role of religious commonality in diplomatic negotiations, particularly with Palestine and Muslim-majority nations. The presence of high-ranking Muslim officials at the helm of South Africa’s foreign policy apparatus may have provided a unique advantage in building trust, deepening engagement, and facilitating diplomatic coordination with key actors in the Muslim world.

Diplomatic negotiations often rely not only on strategic interests but also on shared cultural and ideological affinities. In this context, a common religious persuasion between South Africa’s senior diplomats and their counterparts in Palestine, as well as other Muslim-majority states, could have served as an implicit but significant factor in strengthening relations and fostering collaboration. Religious affinity often enables greater rapport, as it provides a shared moral and ethical framework through which discussions can be framed. This may have accelerated consensus-building, minimised suspicion, and facilitated a more seamless alignment of interests in advancing the ICJ case.

Moreover, in global diplomatic affairs, personal relationships and informal networks frequently influence formal decision-making. Religious solidarity may have played a role in South Africa’s ability to garner support from nations that were reluctant or unable to initiate such legal action themselves. It is plausible that South Africa, leveraging its historical credibility in anti-colonial struggles and its unique positioning within the Global South, found a receptive audience in Muslim-majority states—an audience that may have been more forthcoming given the presence of Muslim leadership within South Africa’s foreign policy establishment.

9.5.4 Balancing National Interest with Religious Ethics

A crucial question that emerges from this analysis is whether South Africa’s move to take Israel to the ICJ was based primarily on strategic national interest or whether personal and ideological convictions, combined with diplomatic religious solidarity, expedited the decision. Did the presence of senior Muslim officials within DIRCO enable smoother negotiations and coordination with Palestine and its allies? If so, does this suggest that South Africa’s foreign policy, at least in this instance, was guided as much by ideological commitments as by geopolitical strategy?

Furthermore, if personal religious convictions facilitated South Africa’s involvement in this case, it raises broader questions about how such dynamics operate in other foreign policy contexts. Would South Africa have been as willing to intervene in international disputes where religious affinity was absent? To what extent does the presence of faith-based solidarity shape the nation’s engagement in global justice initiatives? These are necessary questions that demand scrutiny—not as a critique of the individuals involved, but as a broader inquiry into how deeply personal convictions and shared faith identities influence state diplomacy.

9.5.5 The Precedent and the Diplomatic Consequences

The influence of religious identity on foreign policy is not unique to South Africa. Global leaders from various nations have, at times, been guided by religious ethics in their international engagements. However, when state policy becomes too closely intertwined with personal belief systems, it risks creating a perception of bias that can undermine diplomatic credibility. In the case of South Africa, if the ICJ intervention was significantly driven by the personal religious perspectives of key officeholders and facilitated through shared faith-based diplomatic engagements, it raises legitimate concerns about the long-term implications of such an approach in an officially secular foreign policy framework.

Ultimately, whether or not Pandor and Dangor’s religious affiliations consciously influenced this case, the fact remains that South Africa’s decision has been interpreted—both domestically and internationally—through a lens that includes considerations of religious solidarity. The challenge for South Africa, moving forward, is to ensure that its foreign policy remains balanced, strategic, and resistant to perceptions of partiality, particularly when taking such bold legal action on the global stage.

9.5.6 A Broader Question of Religion in Diplomacy

The implications of this inquiry are not about questioning the legitimacy of the ICJ case but rather about acknowledging a larger, often overlooked reality: the role of faith in geopolitical decision-making. If faith-based considerations—whether implicit or explicit—shape perspectives, then they inevitably influence policy choices, even within a constitutional democracy like South Africa that upholds secular governance. The inquiry into Pandor’s and Dangor’s religious orientations is not an indictment but an invitation to an honest and rigorous discourse about the undeniable role that faith plays in shaping global diplomatic engagements. In a world where religion is frequently downplayed in international relations, South Africa’s case at the ICJ provides a compelling moment for deeper reflection on the intersections of faith, morality, and statecraft.

10. Undeniability of Faith in Geopolitics

Both pro-Israel and pro-Palestinian supporters cannot escape the influence of faith. Religious narratives, sacred texts, and faith-based communities drive advocacy on both sides. Similarly, the Russia-Ukraine war underscores how religious identity shapes nationalistic fervour and justifications for war. South Africa’s diplomatic posture further affirms that while foreign policy is often framed in secular terms, faith remains a potent underlying factor.

10.1 Religious Narratives Shape National Identity and Legitimacy

Faith-based narratives are deeply woven into national identities, influencing both state policies and grassroots movements. In the case of Israel, the concept of a divinely promised land is central to Zionist ideology, while for Palestinians, Islamic heritage and the sanctity of the Al-Aqsa Mosque reinforce their struggle. Similarly, Russia’s justification for its actions in Ukraine is embedded in Orthodox Christian doctrine, portraying Ukraine as an inseparable part of “Holy Rus.” These religious narratives are not merely symbolic; they actively define sovereignty claims, territorial disputes, and the right to exist as a nation.

10.2 Sacred Texts Provide Moral and Theological Justifications for Political Actions

Religious texts serve as foundational sources that influence policy decisions and political rhetoric. The Torah, the Bible, and the Qur’an contain passages that are interpreted to justify territorial claims, resistance, and governance. Christian Zionists cite biblical prophecy to defend unwavering U.S. support for Israel, while Islamic texts reinforce solidarity with the Palestinian cause. In Russia, the Orthodox Church aligns its vision with Byzantine theological continuity, lending divine authority to Russia’s claims over Ukraine. These sacred texts, whether explicitly or implicitly, shape the moral framework within which political decisions are made.

10.3 Faith-Based Communities Drive Advocacy and Mobilisation

Religious communities worldwide play a significant role in shaping foreign policy debates and public opinion. Evangelical Christian support for Israel in the U.S. significantly influences political decisions, shaping diplomatic and military aid. Conversely, the Ummah (global Muslim community) unites in advocacy for Palestine, mobilising political pressure in Islamic nations and beyond. In South Africa, churches, mosques, and interfaith organisations have been vocal in supporting Palestinian rights, influencing national diplomatic stances. The mobilisation power of faith-based groups makes religion an undeniable force in geopolitics, transcending state boundaries.

10.4 Religious Institutions Directly Influence Political Leadership and Decision-Making

Governments often include leaders whose personal faith identities shape their worldviews and diplomatic actions. In Russia, Patriarch Kirill of the Russian Orthodox Church openly supports Putin’s policies, framing the war in Ukraine as a religious mission. In South Africa, the ANC government’s diplomatic stance on Israel is not just shaped by historical parallels with apartheid but also by the faith convictions of key political figures. The presence of religiously motivated leaders in governance ensures that faith-based considerations, whether acknowledged or not, inform international policies.

10.5.Secular Diplomacy Often Overlooks the Deep Religious Motivations Behind Conflicts and Alliances

Traditional diplomatic frameworks tend to approach conflicts through political, economic, or legal lenses, often downplaying religious motivations. However, the durability and intensity of conflicts like Israel-Palestine and Russia-Ukraine suggest that religion is not just a secondary factor but a primary driver of engagement. South Africa’s case at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) against Israel demonstrates that while secular legal mechanisms govern international disputes, faith identities shape the moral imperatives behind diplomatic decisions. A failure to recognize religion’s role in these issues leads to superficial analyses and ineffective conflict-resolution strategies.

11 Conclusion

The evolving geopolitical landscape increasingly reveals that faith is more than just a background factor—it is a central force shaping diplomacy, conflicts, and resolutions. While it is crucial to maintain a secular and constitutional approach to international relations, acknowledging the role of faith provides a more nuanced and realistic understanding of global diplomacy. South Africa’s case exemplifies this reality, demonstrating that foreign policy is not just about law and politics but also about deep-seated faith identities that influence international engagements.

Faith is not a passive or incidental element in geopolitics—it is a driving force that shapes narratives, legitimizes political actions, mobilizes communities, influences leadership, and transcends secular diplomatic frameworks. Recognizing the centrality of religion in global affairs is essential for a more nuanced and effective engagement with international conflicts and diplomacy.

Religion remains an undeniable force in shaping foreign diplomacy. From historical conflicts to contemporary geopolitical struggles, faith-based identities influence international relations in profound ways. Religious realism provides a critical framework for understanding how theological beliefs translate into political actions, often complicating diplomatic negotiations. Moving forward, global policymakers must acknowledge and engage with the religious dimensions of international conflicts rather than sidelining them. Only by integrating faith-based perspectives into diplomatic discourse can sustainable resolutions be achieved in religiously charged geopolitical disputes.

BTh. (Hons-Status) UWC, MA Systematic Theology cum laude NWU, Ph.D. [Politics & International Affairs] UJ.

Lifelong Social and Economic Justice Activist, Christian Theologian, Political Analyst, Published Author & Poet, Freelance Writer, Strategic Advisor and Executive. A former University of Johannesburg SARChi & CADL [Centre for African Leadership Development] Post-Doctoral Research Fellow. Founder of TMOSA Foundation [The Thinking Masses of South Africa] & Founder Anchor host of the RamalaineTalk Blog, on Contemporary Analysis and Comment on Political Discourse in South Africa, including also Global context.