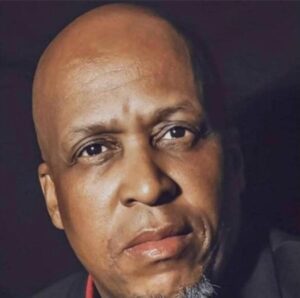

By: Clyde N.S Ramalaine

Contextual Background

The National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) of South Africa, led by Advocate Shamila Batohi, faces mounting criticism for its consistent failure to prosecute what it deems high-profile corruption cases linked to its adopted ‘State Capture’ era notion. The recent collapse of the R280 million Estina Dairy Farm case in August 2024, which resulted in the exoneration of all the accused, highlights systemic prosecutorial deficiencies undermining the NPA’s ability to handle complex corruption cases effectively.

This article builds on a prior collaboration with legal scholar Paul Ngobeni (June 2023), “https://africanewsglobal.co.za/taking-stock-and-keeping-the-npa-and-its-ndpp-batohi-accountable-for-its-disastrous-state-capture-case-prosecution-record/“examining systemic dysfunction in the NPA, including leadership failures, political interference, and fiscal mismanagement. The NPA’s reliance on Commission of Inquiry findings, such as the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture, Corruption and Fraud in the Public Sector including Organs of State, better known as the Zondo Commission or State Capture Commission report, has repeatedly compromised its legal standing, as these findings are non-binding and inadmissible as evidence. Cases such as the Estina Dairy Farm, Gupta extradition attempt, Optimum Coal asset forfeiture, the Nulane and Koko trials reveal a pattern of prosecutorial incompetence. Comparative legal precedents from Canada and Ireland underscore the NPA’s strategic missteps. The Canadian Supreme Court in Canada (Attorney General) v. Canada (Commission of Inquiry on the Blood System) (1997) and the Irish High Court in Goodman International v. Justice Liam Hamilton (1992) ruled that inquiry findings are not enforceable in court, yet the NPA continues to misuse such reports.

The NPA’s failure to secure convictions in all its so-called high profile State Capture, for example, the Estina, Nulane-Sharma, Guptas, Mike Mabuyakula, and Matshele Koko despite significant resources spent, raises serious concerns about its operational efficiency and whether political influences have compromised its prosecutorial independence. Urgent reforms are necessary to restore public confidence through stronger prosecutorial integrity, evidence management, and independent from political influence leadership accountability.

Adding to this, State of the Nation, in its 8 January 2025 publication, featured a lengthy article titled The Case for the Impeachment of NDPP Shamila Batohi and Andrea Johnson.

Calls for the impeachment of Shamila Batohi, the National Director of Public Prosecutions, and Andrea Johnson, the Head of the Investigating Directorate Against Corruption, are intensifying amid accusations of inefficiencies, unjustifiable delays, and questionable decisions. We understand this better when we hear the State of the Nation publication, lamenting Andrea Johnson’s insight as captured in the Amabhungane documentary: “If you look the part and play the part, you will eventually become the part.” This is a nod to the “fake it till you make it” mentality, where projecting confidence is supposed to lead to genuine competence. Yet, the NPA seems stuck in a masquerade, donning a facade of capability while merely masquerading. They aspire for success but are just pretending.”

To underscore the allegations of an NPA in the crisis of credibility, leadership, strategy and tactics and questionable resource spending crisis one may also consider the ongoing case of Durban-based businessman Thoshan Panday and Others.

1. The State versus Thoshan Panday and Others – Durban Central CAS 781/06/2010

The State’s almost 15-year-old case against Durban businessman Thoshan Panday and eight co-accused may exemplify the ongoing systemic failures within South Africa’s National Prosecuting Authority (NPA). The accused face charges linked to the controversial R47 million tender awarded during the 2010 FIFA World Cup for providing accommodation for police officers deployed at the event. Charged with 275 counts, including operating in an enterprise engaged in racketeering under the Prevention of Organised Crime Act (POCA) and corrupt practices under the Prevention and Combating of Corrupt Activities Act (PRECCA), the case has been marred by legal inconsistencies and significant procedural failures. While the case does not meet the criteria of a typical ‘state capture’ matter as outlined by the NPA, it is nevertheless being treated as such.

The State versus Thoshan Panday and Others – Durban Central CAS 781/06/2010 was initially registered in 2010 as a R47 million fraud case. However, this figure is not supported by the State’s commissioned Forensic Investigation conducted by PwC Chartered Accountant and Forensic Auditor Trevor White. The report begins: “As a result of the constraints encountered in reconciling Goldcoast Trading’s supplier invoices with the invoices issued to the SAPS for the SWC, I have provided four scenarios in my analysis to be considered when determining the prejudice or losses sustained by the police due to various misrepresentations made by Goldcoast Trading and Panday.”

White’s forensic analysis, based on detailed calculations outlined in Scenarios 1-4 presented on 24 November 2014, concluded that the actual overstatement by Goldcoast Trading ranged between R2 million and R10.9 million. White’s methodology involved the following scenarios:

• Scenario 1: Calculation of the value of overstated invoices.

• Scenario 2: Calculation of overcharges based on incorrect tariffs applied by Goldcoast Trading.

• Scenario 3: Calculation of potential overpayments to Goldcoast Trading.

• Scenario 4: Calculation of losses after deducting a 20% gross profit margin.

1.2 Compelling Court Order Ruling of 10 June 2024

Despite the State indicating readiness for trial, it has repeatedly failed to provide crucial evidence necessary for the defence to prepare adequately. This evidence, central to the prosecution’s case, involves cellphone recordings and call interceptions, which Panday’s legal defence has contested as unlawfully obtained. The tapes allegedly form the foundation of the State’s case and are now at the centre of a dispute over their legality and the NPA’s refusal to disclose them fully. Since 2021, the accused have persistently requested access to this material, citing their right to examine how the evidence was obtained and its relevance to their defence.

The defence argues that the recordings were secured without proper judicial authorisation, raising concerns that the judge who approved the interceptions may have been misled into including phone numbers unrelated to the case. This has triggered a broader debate on the misuse of surveillance powers and the ethical boundaries of evidence gathering in prosecutorial processes. More concerning, however, is the NPA’s continued failure to comply with multiple court orders instructing it to disclose these recordings. This defiance on the part of the NPA led the accused to seek a compelling order, which was granted by Judge Nompumelelo Hadebe on 13 June 2024, with a 21-day compliance deadline.

In her scathing 10-page ruling, Judge Hadebe criticised the NPA’s refusal to provide the requested information, noting that the State failed to articulate valid reasons for withholding the evidence. The court rejected the NPA’s vague assertions of privilege and concerns over third-party rights, highlighting that the accused’s right to a fair trial was being compromised. Judge Hadebe emphasised the necessity for transparency in criminal proceedings, particularly regarding the circumstances under which the surveillance authorisations were obtained and whether the evidence was legally admissible. She equated the situation to the unlawful admission of a confession obtained without informing the accused of their rights, concluding that withholding the recordings risked undermining the integrity of the trial itself.

The judgment compelled the NPA to provide the requested evidence within 21 days, yet this order has only intensified the concerns over the prosecuting authority’s conduct. Panday’s legal team has repeatedly accused the State of obstruction, noting that several police officers involved in the unlawful interception of phone calls in the matter had previously faced convictions for similar abuses. Panday further alleged that a businessman’s phone number was falsely inserted into the surveillance request, reflecting possible evidence tampering.

This case not only underscores significant procedural failures but also raises broader concerns about the NPA’s institutional accountability and prosecutorial ethics. If the NPA fails to meet its disclosure obligations, it risks further damaging public confidence in the justice system and could see the case dismissed, echoing other high-profile failures such as the Estina Dairy, Nulane-Sharma, and Koko cases. Ultimately, the Panday matter serves as a stark reminder of the urgent need for reform within South Africa’s prosecuting authority, ensuring transparency, procedural fairness, and accountability in the pursuit of justice.

Following Judge Hadebe’s ruling, which was not the first instance where the State had been ordered to disclose legally obtained recordings supporting its case against the accused, the State initially agreed to comply. However, just one day before the expiration of the 21 days mandated by the Court, the State filed a notice of appeal against the ruling.

1.3 The State’s Appeal

In the matter of The State v. Navin Madhoe and Others (Case Number: CCD 06/2021) before the KwaZulu-Natal Division of the High Court in Durban, Judge Hadebe, on 10 June 2024, issued an order compelling the State to provide Accused 4 to 9 with specific information as detailed in Annexure B of the first index to the notice to compel, within 21 days from the date of the order.

However, the State on 28 June 2024, filed a Notice of Appeal against this order on 28 June 2024 and later submitted supplementary grounds for appeal on 27 August 2024. The State’s primary justification for the appeal was based on Section 17(1)(a) of the Superior Courts Act 10 of 2013, arguing a right to appeal the order. Furthermore, the State presented five grounds for its challenge with the ruling.

Firstly, the State contended that the Honourable Court erred by failing to consider its argument that the application submitted by Accused 1 and 3 was defective and not properly before the Court. It argued that procedural deficiencies in the accused’s application warranted its dismissal without consideration of the merits.

Secondly, the State asserted that the Court had erred in its blanket acceptance of the evidence presented on behalf of Accused 1, 3, and 4 to 9, without giving sufficient weight to the uncontested evidence led by the State. The State maintained that its evidence remained largely unchallenged and should have been given more significant consideration in the Court’s determination.

Thirdly, the State argued that the Court misdirected itself in granting a broad order concerning Annexures A and B of the applications, as it had done, relying on the precedent set in S v Rowand and Another 2009 (2) SACR 450 (W). The State contended that the application of this case law was inappropriate in the circumstances of the present matter.

Fourthly, the State submitted that the Court had erred in its consideration of Section 252A of the Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977, which governs the admissibility of evidence obtained through entrapment. The State argued that this provision did not apply to the present case and should not have been referenced in the Court’s reasoning.

Lastly, the State contended that the Court erred in issuing a blanket order regarding Annexures A and B without properly considering or assigning sufficient weight to the evidence presented by the State. It argued that the Court’s decision to compel full disclosure was not balanced against the evidence already disclosed and the broader context provided by the prosecution.

Based on these five primary claims, the State sought to have Judge Hadebe’s order set aside on these five grounds, asserting that procedural and evidentiary misjudgments undermined the fairness of the ruling.

1.4 The Accused’s Counter to the State’s Appeal

The State’s appeal was met with a counter-response from the accused, who submitted their heads of argument outlining the following points:

The accused have challenged the State’s reliance on Section 17(1)(a) as fundamentally flawed, contending that the provision does not apply to criminal proceedings governed by the Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977. Section 1 of the Superior Courts Act explicitly excludes matters regulated under criminal procedure laws from its appeal provisions. The defence argues that the order issued by Judge Hadebe was part of the criminal trial process in the matter of State v. Madhoe and Others, and therefore not subject to the appeal provisions cited by the State.

The accused, jointly charged on 275 counts, including racketeering under the Prevention of Organized Crime Act 121 of 1998 (POCA) and corruption under the Prevention and Combatting of Corrupt Activities Act 12 of 2004 (PRECCA), had formally requested additional information on 28 April 2021. This request aimed to clarify the charges and assist in preparing their defence, in line with their constitutional rights under Section 35(3) of the Constitution, which guarantees a fair trial, including the right to be informed of charges, to prepare a defence adequately, and to challenge evidence.

The State’s initial response on 21 June 2021 did not fully comply, prompting further requests from the accused for additional disclosures on 8 July 2021. Judicial interventions continued, with orders from Judges Henriques, Daya Pillay, and Nkosi between 2021 and 2022 directing the State to disclose the information fully. Despite multiple formal requests and subsequent orders from the court, the State has persistently failed to disclose all relevant information. However, as claimed by the accused, the State continued to provide only partial disclosures, leading to the compel application heard by Judge Hadebe in June 2024.

Judge Hadebe’s ruling was based on the accused’s constitutional right to a fair trial, citing Section 35(3) of the Constitution, which is central to criminal procedure law. The judge specifically acknowledged the accused’s right to be informed of the charges with sufficient detail, to have adequate facilities to prepare a defence, and to challenge evidence. These procedural guarantees, the defence argues, are core to the fairness of a criminal trial and fall entirely within the scope of the Criminal Procedure Act, making the Superior Courts Act inapplicable in this context.

The accused further emphasises that the State lacks the legal authority to appeal such an order within the framework of criminal law. Section 316 of the Criminal Procedure Act grants appeal rights only to the accused, not the State. The only avenue available for the State to contest a ruling would be to apply for a reserved question of law under Section 319 of the Criminal Procedure Act, which permits the court to reserve a legal question for consideration by the Supreme Court of Appeal. However, this provision is limited to questions of law, while the State’s appeal attempts to contest factual matters, further invalidating their grounds for appeal.

The defence has cited authoritative case law, including Director of Public Prosecutions, KwaZulu-Natal v. Ramdass (2019 (2) SACR 1 (SCA)), where the Supreme Court of Appeal affirmed that the State has no general right to appeal in criminal proceedings outside the specific provisions of the Criminal Procedure Act. Similarly, the defence references S v. Rowand (2009 (2) SACR 450 (W)), where it was reinforced that an appeal by the State in criminal trials is not permitted without a reserved question of law.

In summary, the accused argue that the State’s attempt to appeal Judge Hadebe’s ruling compelling the disclosure of evidence is procedurally flawed and legally untenable. The matter falls strictly under criminal proceedings governed by the Criminal Procedure Act and Section 35(3) of the Constitution. As such, the State has no right to appeal and can only seek a reserved question of law under limited circumstances, which it has not pursued in this case. The accused maintain that the State’s continued refusal to comply with disclosure orders violates their constitutional right to a fair trial and obstructs their ability to prepare an adequate defence.

2. What does the Panday Case tell us about the NPA strategy, tactics, and attitude toward court rulings and Availing its harvested evidence?

2.1 Systemic Issues: Leadership and Decision-Making Failures

The leadership challenges during Batohi’s tenure are central to the NPA’s failures. Despite public commitments to revitalise the institution, the NPA has yet to achieve successful prosecutions in any of its state capture-related cases. For instance, in the Panday matter, the State’s failure to fully disclose critical evidence, such as tape recordings, exemplifies repeated procedural shortcomings, often requiring court interventions to enforce basic evidentiary standards. This raises a critical question: Why must the State be compelled by court orders to present the evidence against individuals it has arrested and brought before the court as accused persons? Furthermore, why is the State unable or unwilling to provide the same tapes it deems fundamental to its prosecution? Lastly, it is worth questioning the role, if any, of the NDPP leadership and senior management in this persistent reluctance to comply with evidentiary obligations.

2.2 Accountability and Financial Oversight

Extrapolating from the above, the NPA’s financial stewardship remains a significant concern. The lack of transparent financial reporting on the extensive costs incurred in these high-profile cases continues to undermine public confidence. Perhaps it is time South Africa demanded full disclosure of the NPA’s case-by-case expenditures. Should there not also be a stronger call for accountability measures, including holding the NDPP and senior leadership responsible for instances of wasteful and fruitless expenditure?

The State versus Panday and Others case, among others, exemplifies the State’s willingness to incur avoidable costs, which could have been prevented had the tapes been disclosed from the outset. The Panday case further underscores the NPA’s systemic struggles to manage financial crime cases efficiently and effectively. Initiated over a decade ago, the prolonged proceedings—characterised by repeated delays, primarily caused by the NPA—reflect a persistent failure to streamline case management processes, leading to significant delays in justice delivery.

2.3 Pattern of Procedural Failures and Legal Mismanagement

2.3.1 Duration of the Case

Effective prosecution requires the timely gathering and presentation of evidence; however, the drawn-out timeline in the State versus Thoshan Panday and Others case suggests a failure to balance thorough investigation with procedural efficiency. Extended cases risk witnessing memory degradation, increased costs, and public distrust, further underscoring the need for improved case management strategies within the NPA.

In the Koko case, the court’s refusal to grant a further four-month postponement and its decision to remove the matter from the roll on 21 November 2023 emphasised the importance of upholding the accused’s right to a speedy trial. In light of this precedent, it is reasonable to assert that the same right applies in the State versus Thoshan Panday and Others case, particularly as the State itself appears responsible for delaying proceedings through its reluctance to disclose crucial evidence and its appetite to appeal compelling order rulings. The NPA’s continued failure to provide complete evidence, including the full recordings supporting its claims, directly undermines the accused’s right to a fair and timely trial.

2.3.2 Evidence Management

A core deficiency in the Panday matter, as well as other high-profile cases, has been the NPA’s failure to properly handle evidence. The disclosure of potentially unlawfully intercepted cellphone recordings, which the court may deem inadmissible if found to have been obtained illegally, highlights critical lapses in evidentiary procedures. Effective case management demands strict compliance with evidentiary standards, yet the NPA has repeatedly faltered in presenting evidence capable of withstanding judicial scrutiny to ensure a fair trial. Notably, the NPA appears to be selectively disclosing portions of its recordings rather than the complete content. Could it be that revealing the full recordings might expose procedural errors in how the evidence was obtained? It is well established that evidence obtained unlawfully is generally deemed inadmissible in court.

This poor evidence management not only weakens the prosecution’s case but also exposes the NPA to claims of negligence and procedural incompetence. Is this what the NPA’s Andrea Johnson meant when she was heard encouraging NPA prosecutors ‘to fake it until they make it’?

2.3.3 The NPA’s History of Failure to Comply with Court Orders

The NPA’s failure to comply with the court’s order to disclose its intercepted evidence and instead opting to appeal the ruling reflects deeper institutional issues regarding transparency and procedural integrity.

The 10 June 2023 court ruling and accompanying papers, as shown by the Accused’s Heads of Argument, clearly illustrate a persistent and disturbing pattern of the State’s reluctance to comply with court directives concerning the disclosure of information crucial to the defence’s preparation for trial. The State’s response to the initial request for information on 21 June 2021 (Annexure “TP2” on pages 79 to 82 of the record) failed to provide Accused 4 to 9 with the full scope of the requested information. This partial disclosure led the defence to submit a further request for better particulars on 8 July 2021 (Annexure “TP3” on pages 83 to 94 of the record), in which the outstanding documents and information were again formally requested. Despite these efforts, the State remained non-compliant in fully addressing the defence’s legitimate requests.

The record further shows that following a meeting between the parties on 13 October 2021, the matter proceeded before Henriques J, who, on 30 November 2021, ordered the State to provide all outstanding documents and information referenced in the defence’s prior correspondence (Annexure “TP5”). The State, however, failed to fully comply, providing only partial documentation.

This pattern of non-compliance continued despite subsequent orders from Daya Pillay J on 8 July 2022 and pre-trial proceedings overseen by Nkosi J, culminating in the compel application heard by Hadebe J on 10 June 2024. Justice Hadebe’s ruling reflects a contextual footprint of repeated judicial directives aimed at compelling the State’s cooperation, emphasizing the State’s continued failure to meet its disclosure obligations, thus undermining the accused’s right to a fair trial.

2.3. 4 Assertion of Privilege

Judge Hadebe’s criticism of the NPA’s vague privilege claims revealed a disturbing trend of reluctance to avail evidence under weak legal arguments. The use of such evidence compromises both the legal standing of the case and the ethical standards of prosecution. Respect for judicial rulings and proper disclosure practices are fundamental to upholding constitutional principles, yet the NPA’s actions have demonstrated a persistent disregard for these standards.

The court’s rejection of these privilege claims highlighted a lack of substantive legal justification, suggesting either a poor understanding of privilege applications or deliberate obstruction. Effective prosecutorial conduct requires clarity on what constitutes privileged information and adherence to evidentiary standards. Failure in this area results in case setbacks and raises serious concerns about the competence of the legal teams managing high-profile prosecutions.

2.3.5 Transparency and Procedural Fairness

Judge Hadebe’s ruling explicitly condemned the NPA’s delaying of availing its until now not fully disclosed recordings evidence, emphasizing the importance of procedural fairness. Fair trials are central to the rule of law, and any deviation undermines the integrity of the justice system. The NPA’s repeated lapses in adhering to fair trial principles erode public trust and expose the institution to accusations of bias and misconduct. Upholding transparency is crucial not only for legal credibility but also for ensuring that justice is both done and seen to be done, especially in politically sensitive cases.

2.3.7 The NPA’s Plausible Stalingrad Tactics

The NPA’s frequent reliance on reviewing court rulings, as evidenced in the intended Nulane-Sharma and Koko cases, often appears to lack substantive legal merit and seems driven more by procedural stalling than a genuine pursuit of justice. This approach, characterised by a “blank cheque” culture, enables the institution to engage in prolonged litigation without meaningful internal accountability for how case funds are allocated and expended.

In the Panday case, the NPA’s hitherto repeated refusal to disclose the full set of cellphone recordings—despite multiple court orders compelling it to do so—exemplifies this misuse of legal processes. Such tactics not only delay the administration of justice but also place undue strain on the accused, who are denied access to critical evidence necessary for preparing their defence. The NPA’s failure to substantiate its claims while prolonging cases through reviews and appeals undermines both procedural fairness and the constitutional right to a fair trial, effectively transforming legal proceedings into a drawn-out battle of attrition rather than a principled pursuit of justice. This unchecked expenditure of public resources, paired with the ongoing failure to present corroborative evidence, erodes public trust in the prosecutorial authority and exposes systemic inefficiencies at its core.

The NPA’s procedural delays, exemplified by its last-minute appeal in the Panday case, mirror the same “Stalingrad” tactics the institution has often criticised in other cases. These delay strategies, while providing temporary relief from legal setbacks, ultimately harm the justice system by obstructing timely case resolution. The public perception of justice delayed as justice denied becomes particularly problematic in cases involving corruption and financial crimes. To restore credibility, the NPA must abandon delay tactics and adopt a more proactive, competence-driven approach focused on securing convictions through sound legal practices rather than procedural gamesmanship.

3. Accountability and Financial Mismanagement

The National Prosecuting Authority’s (NPA) repeated failures in high-profile cases such as Estina, Nulane-Sharma, the Gupta asset forfeiture matters, and the State versus Thoshan Panday and Others suggest systemic financial mismanagement and operational incompetence. The South African public remains largely uninformed about the exact amounts the State has spent on these high-profile cases, many of which have collapsed due to procedural errors, evidentiary shortcomings, and trial inefficiencies.

The costs of the State’s commissioned forensic investigation back in 2014 are unknown.

By December 2024, the State’s asset forfeiture process had incurred curator costs amounting to R5.6 million after 18 months of management.

These figures exclude all legal expenses for the period since the first arrest of the accused in 2010, raising serious concerns about financial accountability.

The fundamental question that must be asked is: What has been the proverbial ‘return on investment’ (ROI) for the NPA in the State versus Thoshan Panday and Others case? Are the substantial costs incurred and continuing to accrue—from the initial PwC forensic investigation, the asset forfeiture expenses, and undisclosed legal fees and still to be heard trial—justifiable when the case revolves around an alleged overstating of what The PwC report detailed of between R2.9 million to R10,9 million?

Despite the case not yet being trial-ready due to ongoing delays for which the NPA cannot be exonerated as established in its repeated non-compliance in providing the full recordings as evidence and its habitual appeals against court findings, the State has indicated it plans to call over 100 witnesses. This raises the pressing question of what the ultimate trial costs will be. At what point should such mounting expenditures be deemed excessive, and how is the budget for a case of this nature defined? Or does political manoeuvring come with no accountability for financial waste? At some stage, the leadership of the NPA must be held accountable for the costs incurred and accumulated as a direct consequence of its flawed legal strategies and tactics.

This pattern highlights a broader failure in effective case strategy, trial readiness, and senior leadership oversight. Despite significant legal expenses, minimal results have been achieved in successful prosecutions or asset recoveries, raising serious concerns about financial oversight and the responsible management of public funds.

At what point should the NDPP and senior management be held personally accountable for fruitless and wasteful expenditure? In a previous era, the Public Protector was held liable for personal cost orders. Why has this principle not been extended to the NDPP and her senior leadership team?

The disproportionate expenditure in cases like Panday’s not only reflects a failure of cost-effectiveness but also raises broader ethical concerns regarding the NPA’s institutional priorities. The principle of proportionality in financial management has been blatantly disregarded, with excessive payments to curators and senior counsel diverting critical resources from other pressing legal matters. This imbalance hampers the NPA’s operational efficiency, leaving numerous corruption cases underfunded and deprioritised despite their potential to hold key figures accountable.

Addressing these systemic issues requires a fundamental recalibration of the NPA’s leadership performance and financial management practices. Stricter oversight mechanisms, greater fiscal discipline, and transparent reporting must be implemented to ensure justice is pursued both ethically and financially responsibly. Without decisive reforms, the NPA risks further undermining public trust and its constitutional mandate to deliver justice impartially and effectively.

4. Conclusion

The National Prosecuting Authority’s (NPA) handling of the State versus Thoshan Panday and Others case exemplifies a concerning pattern of systemic failures that extend beyond a singular prosecution, revealing deeper institutional deficiencies. These include political interference, procedural incompetence, and financial mismanagement, all of which have significantly undermined the NPA’s credibility and its ability to deliver justice. The persistence of these issues raises critical concerns about the NPA’s operational integrity and capacity to fulfil its constitutional mandate effectively.

A primary area requiring urgent reform is the establishment of enhanced oversight mechanisms. Independent structures must be instituted to monitor both prosecutorial strategies and financial management practices within the NPA. Such mechanisms should ensure that legal decisions are guided strictly by evidentiary standards and due process, rather than external political pressures or factional interests. This would promote greater transparency and help restore public confidence in the institution’s commitment to justice.

Furthermore, the challenges exposed in the Panday case underscore the need for heightened leadership accountability. A comprehensive and impartial review of Advocate Shamila Batohi’s leadership performance is essential to assess both strategic missteps and managerial shortcomings that have persisted throughout her tenure. This review should address the NPA’s repeated failures to secure convictions in high-profile corruption cases, highlighting whether leadership deficiencies have contributed to the agency’s procedural failings.

Judicial compliance is another critical area requiring immediate correction. The NPA must demonstrate full adherence to court rulings, including the timely disclosure of evidence and avoidance of unnecessary procedural delays. The failure to comply with judicial directives, as seen in the Panday matter where critical recordings were withheld despite court orders, reflects a disregard for the rule of law and undermines the fairness of the judicial process.

The Panday case, much like the Estina Dairy Farm, Nulane-Sharma, and Koko matters, faces a significant risk of dismissal due to procedural errors and mishandling of evidence. Such dismissals, driven by poor prosecutorial decisions, not only deny justice to the public but also waste significant public resources. A consistent pattern of failed prosecutions suggests a systemic problem within the NPA, requiring urgent reforms in legal strategy and case preparation. To prevent further collapses, the NPA must prioritise solid case-building over high-profile asset freezes and ensure stricter compliance with evidentiary standards.

Ultimately, the NPA must transition from a culture of defensive litigation and reactive public relations to one that embodies proactive, transparent, and competent prosecutorial conduct. This cultural shift should prioritise thorough case preparation, legal precision, and respect for both the judiciary and the public’s right to accountable governance. Only through these comprehensive reforms can the NPA begin to rebuild its institutional integrity and effectively serve the cause of justice in South Africa.