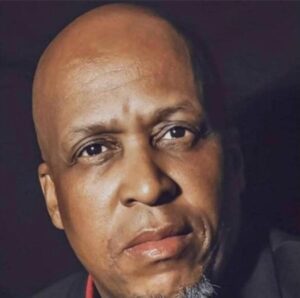

By: Clyde N.S Ramalaine

– A rejoinder to Tshilidzi Marwala’s SA as a possible Third Republic – we can learn from countries like France –

On July, 6 the Daily Maverick carried another of his very interesting op-eds, entitled “SA as a possible the Third Republic – we can learn from countries like France.” UJ Vice-Chancellor Professor Tshilidzi Marwala, a mechanical engineer crowned with a Cambridge Ph.D. in artificial intelligence is no stranger to the SA discourse, this energetic scientist and leader of the University of Johannesburg family is not absent, and his ongoing opinion pieces attest to his undeniable sojourning. Marwala starts by presenting a hypothesis for a rethink of the traditional concept of leadership, which he contends warrants the ingredients of patience and mistakes. In other words, Marwala is preoccupied with a rethink of leadership, a necessity in an epoch when nations across the globe, not excluding the local South African context, which he intends to address, attest to diverse challenges with what they have experienced in leadership.

The reader is introduced and kept in attention to France while pointing to SA as his laboratory. By way of entry and as seen throughout his opinion piece, Marwala postulates France as the society, nation, country, and state to aid the SA journey for a rethink of leadership. Marwala will forgive us for concluding, il est peut-être épris de France, [he is perhaps smitten with France]. Carnot as a founder of the field of thermodynamics and heat engines that we still use in our cars today rightfully enthralls the scientist Marwala. He gladly concedes, “I was also impressed by the work of Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier, which is so central to data analysis today.”

Marwala, asserts: “I have been greatly interested to learn what lessons we can draw from that [French] revolution. To this extent, he affirms: ” One outcome of the French Revolution is that it standardised measurements and gave us kilogrammes, kilometres, litres, etc. I can draw from this lesson that we must be bold in tackling contemporary problems.”

I wish to concur with Marwala regarding the rightful need for leadership to be bold in tackling contemporary problems. We will hopefully return to this later. Marwala then ventures into the status of South Africa in nationhood. His handle for such is better understood in ‘nation formation’. We must surmise that with nation formation, Marwala refers to the process of the forming of the state which he also identifies as incomplete. His reasoning for such is his concession. South Africa is better identified as a multiple nation-state. I would have wanted Marwala to contextualise what these ‘nations’ in one geographic space mean, perhaps its anthropology, ontology, and how successive states since from the 1910 colonial, 1948 apartheid, and including the 1994 Democratic state have for their own truths continue to uphold.

I had wanted Marwala to pause and help us (his readers) appreciate this claim in truism, fallacies, idiosyncrasies, and shibboleths. The primary reason for imploring Marwala to be more forthcoming on this subject may be my locating of his leadership theme as devoid of this interstice and thus renders what is considered traditional leadership questionable. Marwala proceeds to talk about a South Africa in-nation definition that he identifies as a central goal to be a first-world country. Marwala contends, “In South Africa, the issue of nation formation is that it is incomplete, with many nations inside a nation. He correctly identifies the imperative to work hard in what he identified as the political, economic, technological, and social spaces as the measurements for such first-world success status. Yet his hard work does not remotely engender the dynamism of activism as a key ingredient.

As noble as Marwala’s plea for a rethink of leadership purports to be, his idealism of a ‘first-world country’ as the sum-total of a South Africa in a future of description presents more challenges than answers. Unlike the general public, academics do not share the privilege of merely resorting to using or regurgitating constructs. His usage, therefore, of ‘nation,’ ‘first world,’ ‘meritocratic country,’ and ‘traditional leadership’ without defining his understanding of such leaves us none the wiser. The writer assumes that there is consensus on these constructs.

Let us hear the scholar Marwala, as he categorically asserts, “As a nation, we must set out our goal, which should be to become a first-world country and work hard in the political, economic, technological, and social spaces to achieve this.” He says, ” One of the difficult decisions we must make is building a meritocratic country where we only put forward the best talent. Marwala again strays down a Cinderella path without explaining his usage of a ‘meritocratic country’ nor what he frames as the best talent for describing SA in future pursuits. The problem with this assertion lies not in its plausible honesty of intention but its potentially ahistorical, if not precarious, crude assumption tantamount to airbrushing South Africa in history before 1994 and beyond. I had wanted Marwala to categorically state for the record that the best talent is and remains our youth, that unfortunately is defined in unemployment statistics of plus 66%. I wanted him to bemoan how any nation could hope to attain progress when the leading party rejects youth leadership and is a serial offender of gatekeeping.

The ANC-led state long ago shared its idealism for a South African nation as best understood as a democratic, non-racial and non-sexist society. One hears it as, “A non-racial South Africa means a South Africa in which all the artificial barriers and assumptions which kept people apart and maintained domination are removed. In its negative sense, non-racial means the elimination of all colour bars. In positive terms, it means the affirmation of equal rights for all” (http://www.anc.org.za).

Any careful analysis of the South African society will highlight the complexities, structural intricacies, confusion, and this idealism as practical reality since the content of non-racial until this hour in the ANC remains a conflated, lazy, hashed, and over-abused rhetorical construct. I had wanted Marwala, the scholar, to give us at least a definition of the construct of the nation understood through the window of nationalism that he advances in his quest for SA. A D. Smith, a recognised scholar with a comprehensive body of work, contends, “Nationalism is an ideology and movement that promotes the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), especially with the aim of gaining and maintaining the nation’s sovereignty (self-governance) over its homeland” (Smith 1998:225).

Perhaps to underscore this complex notion of a nation that often makes for a chakalaka mix understanding of non-racial, we must hear the ANC’s longest-serving president, Oliver Reginald Tambo, unfortunately in incoherence for his handle of what non-racial means as he was asked back in 1985. “There must be a difference. That is why we say non-racial. We could have said multi-racial if we had wanted to. There is a difference. We mean non-racial rather than multi-racial. We mean non-racial- there is no racism. Multi-racial does not address the question of racism. Non-racial does. There will be no racism of any kind and, therefore, no discrimination that proceeds from the fact that people happen to be members of different races. That is what we understand by non-racialism” Oliver R. Tambo – 1985

I had wanted Marwala to consider the reality of the conflicted ANC as leader of society. A conflict some trace back to its establishment and evidence in its early priorities. Of these priorities, some of us hold, “Few historians will dispute that the ANC in its genesis in 1912 evidences a leadership that unequivocally assimilated as African elites, who no longer wanted to be side-lined and subjugated by white colonial masters, but who were not averse to making deals with the colonial powers in order to achieve their objectives. Thus, some of the most important activities of the early leadership of the ANC were to dispatch delegations to petition the British monarch and parliament for fairer treatment and recognition” (Ramalaine and Niehaus January 9, 2018, Pretoria News).

In my most recent seminal piece, I asserted, “It is important to recognise the earliest means for a constitutional frame for a future South Africa as articulated by the ANC in its 1991 Constitutional Principles for Democratic South Africa. In this forward-looking visionary articulation, I encountered the reflection of the values attributed to non-racialism of unity, humanism, humanitarianism, and nation-building: In a follow-on to the espoused ideals of the ANC as articulated in its Constitutional Principles for a Democratic South Africa, otherwise understood as a nation, the adoption of the South African Constitution in 1996 marked another significant moment of solidifying the system of democracy for governance for a state that recognises the race paradigm as permeating reality for identity formulation. Chapter 1, Section 1(b) states, “The Republic of South Africa is one, sovereign, democratic state founded among others on the following values (b) Non-racialism and non-sexism” (Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996). The interim Constitution remains the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Act 200 of 1993.

I had hoped I did not need to remind Marwala that the struggle for liberation and humanity in South Africa for those classified as lesser human beings was a bloody and sordid affair. VC Marwala wants to remind us how bloody the French revolution was. Perhaps we need not be reminded of how bloody the French revolution was. The French Revolution started on May 5, 1789, and was concluded by 9 November 1799. Meaning (10 years, 6 months, and 4 days).

Meaning how does one compare its almost 11 years with more than 350 years of oppression, subjugation, and disenfranchisement that showed no regard for the Aboriginals who were declared vermin at some stage—robbed of their land by those who arrived on ships until SA was under the control of Dutch-led DEIC, the subsequent 1820 British Occupation that predates 1910 Colonial state. The latter, known for its capitalism-driven greed fuelled by the violence of a gold rush for which a labour force had to identify. Lastly, not discounting the brutality of the 1948 heretic apartheid regime that in eugenics thinking separated the people of South Africa under its truth of law and order in a separate development.

Sir, this is our own bloody gory story unless the black elites have bought into the airbrushed watered-down version as the metanarrative of this era. May I say again colonialism and apartheid were brutal violent systems that were necessarily bloody for those who suffered under them? That is our history, and it’s from that history that we are struggling to find a way to equality, which often attests to a mirage for the black majority. So, when Marwala talks about the meritocratic country, does it take necessary cognisance of this past that even the constitution refuses to name for what it is. When he talks of that meritocratic country is it from the cradle of neo-liberal thought or where does it link with our past in pasts? Our quest for bold leadership can never omit or glibly ignore this reality of history less in romanticising it but by consciously challenging us to do better.

Marwala makes a bold deduction: “South Africa is undergoing a political civil war that can derail progress. We are not sure how this political civil war will culminate. Some suspect it will usher in a genuinely multi-party democracy that will reduce the excesses of corruption and enrich our democracy. Some think it will lead to the Third Republic, where the virtues of democracy, economic prosperity, and human solidarity will fundamentally become South Africa’s culture.

This mouthful from my learned friend comes riddled with conclusive assertions of political civil war, progress, and democracy. He ventures to allude to Zimbabwe as the maximum symbol of a failed state, in tones of similar neo-liberal syntax.

Marwala is meticulously careful not to admit that the proverbial train has long lost its tracks. He will forgive me for concluding that he is consciously politically correct not to share his honest analysis of a derailed transformation imperative, the challenge of justice as an opaque reality for the masses, as articulated by Lindiwe Sisulu in her January 6 article. Lest we forget, how Sisulu sets out to engage the constitution with a poignant opening statement, “Let’s not fool ourselves and one another; the primary motivation for the evils of colonialism was and still is economic. It is organised crime, the robbery of other people’s land and resources, as well as the exploitation and use of their labour. It is also about the reduction of these people to mass consumers and exclusion from the ownership of the factors of production and wealth creation.” (Sisulu, L, IOL Daily News, January 6, 2022)

Professor Marwala is eerily silent on the validity of economic redress as an imperative. The scientist Marwala, who advocates for bold leadership is seemingly hushed on ethical leadership and fails to red-card a SA president [Cyril Ramaphosa] accused of grave crimes of kidnapping, money laundering, and bribery besides flouting section 96 of the Constitution. Why is Marwala silent? Where is his boldness as he advocates SA must be evidence in leadership?

Marwala’s French romantic labyrinth of a meandering journey takes us to the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre famous for “existence precedes essence.” Marwala is yet to explain to us his notion of the Republic as a defendable means and form of description for South Africa despite its historical context that can be traced back in firstness to 1961, and for which he accredits its second coming in a 1994 moment. Out of the debris of these two constructed realities of republics, Marwala seeks to contend for a third republic, the same he is less clear about except for his idealism of a ‘first-world country’s status as a goal, in which SA will confirm a meritocratic country.

Marwala, then in Marxian draped kaftans stance, almost prophetic sense, implores South Africa to acknowledge the gains of the Post – 1994 democratic era. He equally cautions South Africa on the anomalies of this era. He does not omit the glaring failures of the post-1994 political leadership immanent in ‘the inability to offer a secure supply of electricity, failure to tackle inequality, and failure to sufficiently grow the economy to tackle unemployment.

Marwala reminds South Africa of another lesson it can learn from France in the arena of great scholarship. “Scholarship that advances social, economic, political, and technological progress.”Marwala asserts that “progress requires engineers and scientists to chart a route to economic development and secure, reliable energy and water. We must populate all spheres of influence with thinkers, doers, technologists, and scientists. Africa’s underdevelopment can partly be explained by a lack of scientists, engineers, and scholars in powerful positions.” The theologian in me wanted to shout hallelujah, but I then realised Marwala is not as bold as he purports to be. As much as he reminds SA of a need for bold leadership, he himself is yet to take that lesson from his beloved French nation, leadership, and heroes like Bonaparte. Any time a scholar engages in the critical components of society in deconstructing of colonialism, he/she is expected to engage a multiplicity of spheres and dimensions. Still, it is expected that he/she will be brutally honest about the space they claim their own for expertise. Here, I expected Marwala to be frank about the lack of transformation at institutions of higher learning. I wanted him to reflect on the retarded pace of transformation, not measurable in sheer VC individual status but the reality of the grave problem. I wanted Marwala to concede how black leadership at the helm of institutions of higher learning meant very little if the terms of Mamphele Ramphele and Njabulo Ndebele at UCT could be used as a yardstick. Lest we forget it is the acceptance of a status quo, by these black ‘jewels’ for some that in reality produced the #FeesMust Fall campaign and the Decolonisation of Education quest at UCT. It would be interesting to look at the statistics of comparative professor designation level black-to-white teaching staff. Why is Marwala not bewailing this ongoing reality at most institutions of higher learning?

Thus, my deduction, when those like Marwala call for a meritocratic country, they often consider themselves not products and beneficiaries of the empowerment and transformation imperative and readily assume they arrived in these positions at the bastions of learning [in reference to 500 years since the Reformation] in their own boots. The problem with this belief system is that it divorces the beneficiaries like Marwala in a similar vein as his white counterparts to then pontificate on black leadership from an aloofness.

I had wanted Marwala to tell us why Eskom CEO Andre De Ruyter, its COO Jan Oberholzer, and the entire Eskom Board deserves to be in any position at Eskom considering the grave lack of service delivery and disservice South Africans are subjected to. Marwala skirts around these pertinent issues in forms of escapism and lacks the courage of his conviction, to be honest, to call a spade a spade. Instead, he takes comfort in political correctness, obviously not too interested in rocking the boat. Professor Marwala, where is the bold leadership you encourage SA to draw from the French?

Marwala advocates for building a global system of innovation, emphasising linking universities worldwide to each other and to other centres of influence such as industry, multilateral organisations, and government agencies. We should create an ecosystem of staff and students to facilitate exchanges, mobility, research, and tackle global problems such as climate change. The only problem is that Marwala is absent in the environment explanation for this vision. He pretends not to know how arrogant academics can be when students would challenge them. He furthermore acts SA as a space of equality where innovation does not need wifi- connectivity, tools, equipment, and access. These are things the black child, to a large extent, is denied despite Marwala and a slew of other black VCs. In the heat of the COVID epidemic, I asked the MEC of Education, Panyaza Lesufi, why I, as a citizen, cannot sponsor a fellow student in sharing the data I have access to.

It is common fact that in SA subscribers and customers of SA cell phone operators are denied their right to transfer data. Lesufi, while concerned, mumbled some political claptrap in the nothingness of any substantial response because political leadership is wholly out of touch with the masses. But if I condemn political leadership, I am compelled to ask why scientists in the academic institutions have shown no agency to flag this anomaly and to engage the cellphone service providers on the matter directly. I am concerned about why they equally failed to engage political power on the matter. At last, I concluded the idea of innovation is a nicety that is deliberately kept separate from its need for activism. I wanted to know where is the academic activism of Marwala et al.

Let us hear Marwala’s last lesson: “The last lesson we can learn from France is how to build educational institutions.” Clearly, Marwala is absent in centralising my earlier contention of the transformation agenda as an imperative.

I got to the end of Marwala’s musing with a sense of mixed but troublesome questions. Did Marwala explain his epistemology of traditional leadership, let alone remythologizing such for a useful future of SA? Is Marwala not making several disturbing assumptions about what defines SA in the quest to be a nation? Is Marwala also not moving from a particular assumed context that he either consciously cannot in boldness critique or embrace as his cradle?

What is the relevance of the notions of a debate on 2nd and 3rd Republicans for South Africa as identity markers? Why does this decorated scholar fail to problematise – why is Marwala, the scholar, obsessed with uncritically defending this republic? Is his frame of leadership uniquely reserved for black political leadership – if not, where is his criticism of the economy, which is not led by black political leadership? Where is his outright critique of institutions of research and development which still largely are controlled by the beneficiaries of colonialism and apartheid? Where is his agonising for the distorted land ownership question?

I wanted to understand from Marwala what a republic, which he takes ease of comfort in, would mean outside and devoid of the historical frames of colonialism and colonisation. His view of what South Africa needs in academics appears less sophisticated but generic, which stands cold to the complexities of the attending race reality that continue to define SA. Equally, the scholars and academic spaces he envisages for South Africa stand naked in acknowledgment of the complexities, contradictions, shibboleths, and absenteeism of black academics to challenge the status quo in the boldness of leadership as he prognosticates. Unfortunately, Marwala gives us no example of any other nation, let alone an African country that has made advances in the spheres of leadership. I wanted Marwala, the scientist, to point us to Kenya’s sterling work in technology advancement

Lastly, I wonder how Francophone countries read Marwala, African nations who long after colonisation remain trapped and cannot rid the control of his beloved France. Yet let me not go that far, but can we bring it home. I would remind Marwala of the dastard acts of French scientist George Cuvier, a naturalist. This racist, empowered by the demon of colonialism, became obsessed with studying the naked anatomy of our great Mother Sara Baartman as a science specimen. His depraved mind and lust saw that from March 1815, Mother Sara was explored by French anatomists, zoologists, and physiologists. Cuvier concluded that she was a link between animals and humans. Thus, Mother Sara was used to help emphasise the stereotype that Africans were oversexed and a lesser race. As a self-identifying KhoeSan, that is my summary of France, and I struggle to learn lessons from Marwala’s beloved France because it is more than personal for me.

Instead, an empowered beneficiary of the transformation imperative as VC opts to celebrate France the imperial force, the pillager, and the Haitian destroyer all of which went in parallel with the change from one republic to another.

A published author and poet, strategy design consultant/advisor, speechwriter, and lifelong social and economic justice activist, he makes up part of the 80’s student leadership in a Cape-based student- led push for the overthrow of apartheid. His counsel is often sought by senior politicians, ambassadors, business executives and clergy. In 2010 Former President Thabo M. Mbeki twice wrote to him personal notes. . In 2017 former President Jacob G. Zuma twice invited him to one-on-one meetings to discuss the SA discourse and the role of religion in SA politics. The former ANC Secretary-General now Chairperson, Gwede S. Mantashe invited Ramalaine in 2012 into a panel of thought leaders that held its first meeting at UJ Soweto Vista Campus to advise on ANC policy positions. On August 28, 2015 he was approved by the ANC Deployment Committee to serve as an ambassador – unfortunately the appointment never was finalised. He is a licensed and ordained Theologian with credentials both in the SA (1992) and USA (2005). His gifted expository preaching is celebrated in audiences wider than South Africa. He Holds BTh (Hons) UWC, MA Systematic Theology (Cum Laude) NWU, with a Dissertation: “Black Identity and Experience in Black Theology: A Critical Assessment.” Ramalaine recently completed his Ph.D. in Politics and International Affairs as a SARCHi Candidate. His thesis: “South Africa’s State-Led Race-Based Social Identity Construction: A Critical Assessment.” He is a public intellectual who often is invited by media-houses, TV stations, and community radio stations to share his analysis and comment on contemporary developments in political or religious discourses, with more than 1000 published articles on primarily diverse media platforms. His incisive and thought-provoking opinion pieces are welcomed as part of creating an alternate voice in SA discourse. His other work has appeared in The Thinker – Africa’s leading Journal in African thought.